Every trusted name you recognize follows an invisible framework at the heart of brand strategy.

Think about the last time you picked something off a shelf or downloaded a new app.

Did you choose it because the icon looked appealing? Or because the name was already familiar and trusted?

More often than not, it’s the latter.

That invisible hand guiding your trust is called brand architecture.

We rarely notice it consciously, but brand architecture shapes our choices every day. It is the blueprint of trust, a system that tells you whether a new product belongs to a company you already know or an unfamiliar name.

Companies spend years designing how their brands relate to each other: which names stretch across everything, which stand alone, and which carry a seal of approval. Get this structure right, and every launch builds on existing trust. Get it wrong, and you end up spending millions explaining who you are while customers wander off in confusion.

What Is Brand Architecture? (Definition & Meaning)

The definition of brand architecture is the system a company uses to organize and present its brands, sub-brands, and products so customers instantly understand the relationship between them. It’s less about a clever name or a logo and more about the system behind them. A system that reduces marketing costs, speeds up adoption, and gives customers clarity at the moment of decision.

If you’re in FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods), fintech, hospitality, SaaS, or automotive industry, brand architecture isn’t just a strategy. It’s a growth engine. In these industries, customer choice, acquisition costs, and loyalty depend heavily on whether people can navigate your portfolio quickly and confidently.

Types of Brand Architecture (Models & Examples)

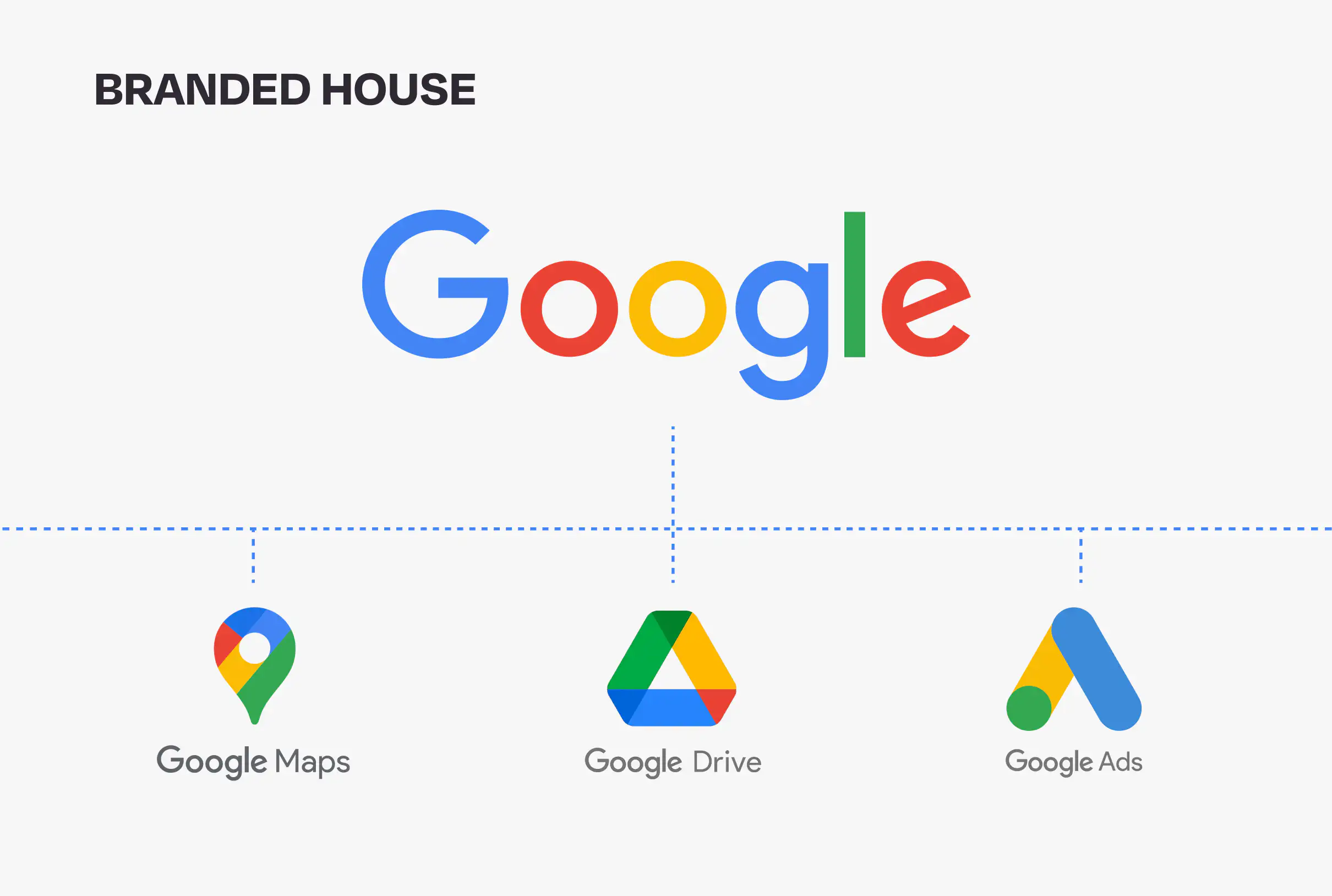

1. Branded House: One Name, Many Extensions

A Branded House stretches one powerful masterbrand across multiple products. Every offering borrows strength from the parent, and in turn, adds equity back to it.

Tesla is a brand architecture example of a Branded House: cars, batteries, and charging stations all carry the Tesla name. Each product reinforces the same story of innovation and sustainability.

The same is true for Google, whose suite, Google Maps, Google Drive, Google Ads, ties back to a single brand identity.

The advantage is efficiency. According to NIQ’s BASES analysis, 96% of breakthrough product winners were brand extensions, not new-to-the-world brands. Consumers adopt familiar names far faster than unknown entrants.

Pros of Branded House

- Strong parent brand equity transfers instantly to new products.

- Lower marketing spend compared to building new brands.

- Faster adoption and cross-sell opportunities.

- Consistency creates customer trust and clarity.

Cons of Branded House

- Reputational risk is shared across all products.

- Limited flexibility to target different audiences or price points.

- Difficult to reposition individual offerings if the parent brand shifts.

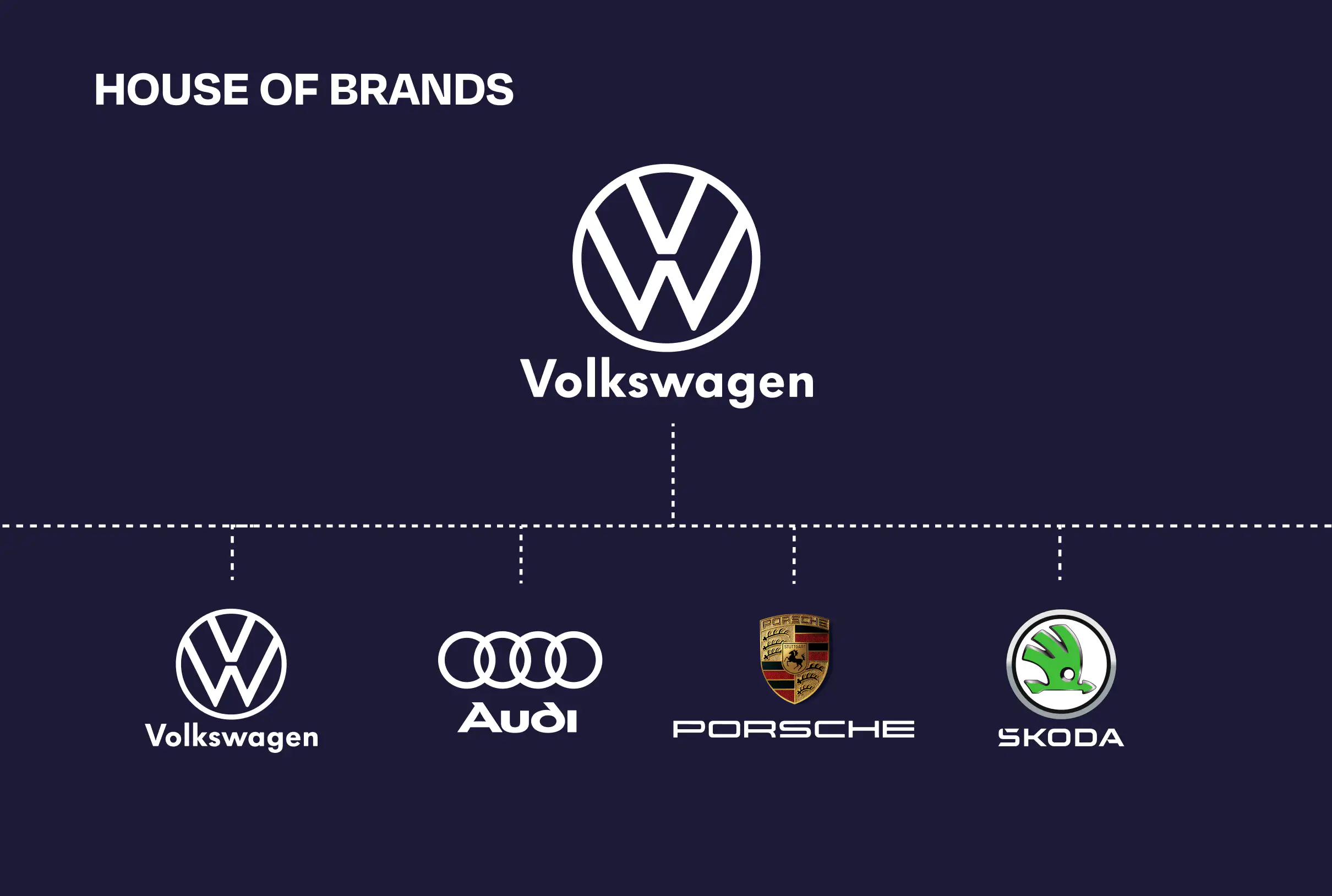

2. House of Brands: Many Names, One Parent in the Shadows

In a House of Brands, the parent company fades while each product stands independently.

Unilever owns Dove, Axe, Sunsilk, and Hellmann’s. Each of Unilever’s 400+ brands speaks to different audiences without diluting the other.

Volkswagen Group does the same: VW for mainstream, Audi for premium, Porsche for performance, Škoda for value. By separating brands, Volkswagen serves multiple markets simultaneously, and shields itself when one brand stumbles.

This separation also protects the parent from reputational risk. If one brand stumbles, the others remain intact.

Pros of House of Brands

- Each brand can target a unique audience or market segment.

- Reputational risk is isolated. One failure won’t harm others.

- Easier to experiment with positioning, pricing, and identity.

- Allows premium, value, and niche brands under one portfolio.

Cons of House of Brands

- Higher marketing costs since each brand needs separate investment.

- Less synergy: brands don’t automatically strengthen each other.

- Customers may not connect the dots back to the parent company.

- Complex to manage across large portfolios.

3. Endorsed Brands: Independent, but With a Seal of Approval

Marriott runs Courtyard by Marriott and JW Marriott, distinct experiences, unified by trust. After acquiring Starwood, this structure helped it integrate seamlessly into the world’s largest hotel company with over 30 brands.

In SaaS, Atlassian takes the same route. Jira by Atlassian and Confluence by Atlassian feel distinct, but users know they’ll integrate smoothly.

Endorsement works best when credibility from the parent lowers barriers to entry, while sub-brands provide differentiation.

Pros of Endorsed Brands

- Gains trust and credibility from the parent endorsement.

- Sub-brands retain some independence in identity and positioning.

- Good balance between efficiency and differentiation.

- Easier to integrate new acquisitions into the parent’s ecosystem.

Cons of Endorsed Brands

- Overuse can blur customer perception (too many “endorsed by…”).

- Still shares some reputational risk with the parent.

- May create confusion if endorsement value isn’t clear to customers.

4. Hybrid Brand Architecture: Mixing It Up

Most large companies end up here. Some brands stay tied to the parent; others stand alone.

Coca-Cola Company runs Coca-Cola as a flagship while Sprite and Fanta thrive independently. Alphabet houses Google as a branded house, while moonshots like Waymo or Verily keep distance. Toyota sells Corollas under Toyota, while Lexus sits apart, sustaining a $20,000+ price gap in the US.

Hybrid systems give companies flexibility, protecting crown jewels while experimenting elsewhere.

Pros of Hybrid Brand Architecture

- Maximum flexibility to manage different brand strategies.

- Shields crown jewel brands while enabling innovation.

- Can combine efficiencies of a Branded House with the reach of a House of Brands.

- Useful for conglomerates with diverse markets and acquisitions.

Cons of Hybrid Brand Architecture

- Most complex model to manage and communicate.

- Risk of customer confusion if boundaries aren’t clear.

- Requires strong governance to maintain portfolio clarity.

- Can be resource-heavy to balance multiple approaches.

How to Choose the Right Brand Architecture Strategy

The right model depends less on creativity and more on clarity, risk, and efficiency. Ask:

- Do we want one story or many? – Branded House if all products share the same promise. – House of Brands if audiences and price points diverge.

- How much reputational risk can we share? – Branded House concentrates both equity and risk. – House of Brands spreads risk but requires more investment.

- Do we need speed or precision? – Branded House speeds adoption, lowers CAC. – House of Brands allows precise positioning.

- Are we expanding or acquiring? – Endorsed and Hybrid architectures help integrate new ventures without confusing customers.

Different industries lean toward different models. In FMCG brand architecture, companies often favor a House of Brands (like P&G or Unilever) to keep products distinct and reduce risk, like P&G’s detergents or Unilever’s personal care portfolio. In SaaS brand architecture, players usually adopt a Branded House or Endorsed model, where trust and seamless integration are critical. Automakers tend to go Hybrid, separating luxury (Lexus, Audi) from mainstream (Toyota, VW). Hospitality companies thrive on Endorsed brands, where Courtyard by Marriott signals a different experience without losing the Marriott seal of trust. In fintech, speed and adoption matter most, so a Branded House usually wins.

Why Brand Architecture Is Important for Business Growth

1. Conversion Clarity

Customers convert faster when they instantly know what a brand stands for.

- FMCG: Procter & Gamble separates Tide, Ariel, and Gain to reduce confusion in the detergent aisle.

- Fintech:Revolut extends its brand across banking, trading, and insurance, letting users adopt new services without hesitation.

- Hospitality: Marriott’s tiered brands make booking frictionless, since travelers can identify the right level of service immediately.

2. Lower CAC

When you launch a new Google product, it inherits billions of users and a strong reputation. That’s low CAC. By contrast, a House of Brands like Unilever invests separately in each name, but the payoff is precision, each brand hits its target segment directly.

3. Pricing Power

When structured well, brand portfolios protect margins. Toyota can sell a Corolla and a Lexus to the same household, capturing different budgets without cannibalizing either. Coca-Cola clearly distinguishes Classic, Zero, and Diet, avoiding price erosion while serving health-conscious consumers.

4. Cross-Sell & Lifetime Value

Good architecture encourages customers to stick around and expand usage. Atlassian’s products signal compatibility, boosting attach rates. Square connects merchants using its terminals with consumers on Cash App and Afterpay, growing LTV across ecosystems.

5. Faster Expansion & M&A

Clear structures make entering new categories or integrating acquisitions smoother. Alphabet shields Google while incubating riskier bets. Marriott’s endorsed model allowed it to merge Starwood properties without confusing loyal guests.

6. Risk Containment

If Volkswagen faces a recall with one brand, Audi and Porsche are insulated. If Axe’s edgy campaign sparks controversy, Dove remains unaffected. This separation protects the crown jewels of the business.

The Growth Blueprint

Your next product launch will either borrow from a bank of trust you’ve already built, or start from zero.

Brand architecture decides which it will be.

Frequently Asked Questions on Brand Architecture

What is the definition of brand architecture?

Brand architecture is the system a company uses to organize and present its brands, sub-brands, and products so customers clearly understand the relationship between them. It provides clarity at the moment of choice and guides trust across the portfolio.

What are the types of brand architecture?

There are four main types of brand architecture models:

- Branded House (e.g., Google, Tesla)

- House of Brands (e.g., Unilever, P&G)

- Endorsed Brand Strategy (e.g., Marriott, Atlassian)

- Hybrid Brand Architecture (e.g., Coca-Cola, Toyota, Alphabet)

What is the difference between a Branded House and a House of Brands?

A Branded House uses one powerful master brand across multiple products, creating efficiency and trust (e.g., Google Drive, Google Maps). A House of Brands separates products under distinct names, targeting different audiences and reducing risk (e.g., Dove, Axe, Sunsilk under Unilever).

How does brand architecture affect growth?

The right brand architecture boosts conversion clarity, reduces CAC, protects margins, increases cross-sell opportunities, and insulates the business from reputational risks. In short, it directly impacts the bottom line.

What is an example of brand architecture?

A simple example is Tesla, which follows a Branded House model. All its products, cars, batteries, and charging stations, share the Tesla name. On the other hand, Unilever is a House of Brands, where Dove, Axe, and Sunsilk operate as independent names under one parent company.

Which brand architecture model is best for SaaS or FMCG companies?

In SaaS brand architecture, companies often choose a Branded House or Endorsed model, since trust and seamless integration are critical (e.g., Jira by Atlassian). In FMCG brand architecture, firms usually favor a House of Brands to keep products distinct and reduce risk (e.g., P&G’s Tide, Ariel, and Gain).